Introduction

We, the folks behind the words and operation of Learn Grant Writing, are always striving to improve our skills right alongside our students. One relatively new-to-us concept we’ve been really loving is strength-based writing. Writing a powerful grant narrative is a fine art of demonstrating urgency and story-telling. Strength-based writing is challenging our idea of what story we’re telling and how much focus we’re dedicating to urgency in our grant narratives.

Deficit-based (wrong) versus strength-based (strong) writing involves a shift from focusing on what is broken to instead focusing on what is working. In the research world, this is known as deficit-based thinking versus strength-based thinking. Essentially, awareness of these concepts helps grant writers balance the importance of illustrating the urgency of a problem to be solved with the importance of using positive language in a grant narrative.

We’ve done some of our own research and also had a wonderful conversation with Kate Hohman Billmeier of Wellspring Group Consulting on the topic. She doesn’t claim to call herself a deficit-based versus strength-based expert, but she is highly skilled in evaluation and field trained in adopting a strength-based approach. She’s seen the positive impact of strength-based thinking and is a firm believer. Thanks for your insight for this post, Kate!

Why Does Strong Writing Matter?

In our efforts to be continuously learning, we’re not afraid of taking a bite out of humble pie. In fact, we’ll even show you a real world example of the dangers with wrong writing! Below is an excerpt Meredith wrote a few years ago. Although the grant was funded, when we look at the application now all we see is how it is steeped in deficit writing.

This excerpt is from a grant application to the U.S. Department of Environmental Protection Agency for brownfield redevelopment grant funding:

“Because Anchorage grew so fast with the construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, the area lacked land use policies and enforcement resources. When oil prices dropped in 1986–88 it caused the ‘Great Alaskan Recession’ where nearly one in ten jobs were lost. Businesses folded and abandoned their properties and to this day, many remain vacant. Known and suspected contamination on these sites has impeded their redevelopment and depressed property values... The former 4th Avenue Theater in Downtown is a cherished historical icon but rapidly deteriorating. It has numerous code deficiencies, asbestos, and a petroleum release from an underground storage tank. Many downtown businesses have relocated to midtown leaving brownfields in their wake.”

Did that catch your attention? Do things seem dire?

Yes and yes. However, should that be our only or even primary goal? Eh, not such an easy yes. Is there anything in that excerpt that makes you want to visit Anchorage or think positively about Anchorage? Quite the opposite, even though the city Anchorage does have a lot going for it.

This excerpt defines Anchorage by its worst characteristics. Imagine talking about people in this same way; imagine talking about yourself in this way! When we focus all our attention on negative facts and major gaps, this has the effect of “othering”. We are easily tempted to view or treat a person, group of people, or place as intrinsically different from and alien to oneself. Mackenzie Price from Frameworks Institute said this often reinforces the negative stereotypes that organizations using the language are working against.

Going even further, wrong writing can lead readers to believe that these negative characteristics are inherent rather than the result of circumstances. This can encourage a system where people and places are treated less as multi-faceted partners in a project or program and more like simplified objects of charity.

How could we have written that excerpt in a way that explained the problem while also weaving in the reality that there is a good team behind the project, solid momentum, and other available resources? Because that was the whole truth of the project.

Strength-Based Writing ≠ Positivity Whitewashing

First and foremost, we must understand that strength-based writing is not simply removing all challenges or problems from our grant application narrative. It is safe to say that pretty much every grant application will require applicants to describe the problem faced by the applicant. After all, funders want to ensure their dollars are going towards good, impactful work.

Miriam Axel-Lute, Editor, Shelterforce and Associate Director, National Housing Institute highlights several dangers of using only positive language in her article The Opposite of Deficit-Based Language Isn’t Asset-Based Language. It’s Truth-Telling.

When we only use positive language, we fall into the narrative of pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps or bootstrapping. “...if everything is so great, what’s the problem? Why are we putting resources there? If we don’t name the harm that has been done and assign responsibility, are we really undoing the perception that populations and neighborhoods in trouble brought it on themselves?,” said Axel-Lute.

Thus, we must push for something much more subtle and powerful than merely using only positive language. Grant writers must still describe deficits, problems, and challenges faced by the people or group served by an organization. A strength-based approach prompts us to shift focus to build on strengths rather than continue grinding on deficiencies of the community we’re hoping to serve. Put another way, this practice is more of a balance rather than an either/or. We need to aim to be truth-tellers.

Furthermore, this practice extends beyond the wording you choose in your narrative, as it ties back to how a program is developed and implemented. We’ll cover a bit of that below, and Meredith talks more about it in the second edition of How to Write a Grant: Become a Grant Writing Unicorn.

Start With Mental Models

To understand how to develop strong writing, we need to know our own personal mental models. The following paragraph is an overview of mental models according to Jones, N. A., H. Ross, T. Lynam, P. Perez, and A. Leitch:

“Mental models are personal, internal representations of external reality that people use to interact with the world around them. They are constructed by individuals based on their unique life experiences, perceptions, and understandings of the world. Mental models are used to reason and make decisions and can be the basis of individual behaviors. They provide the mechanism through which new information is filtered and stored.”

Or, Rouse and Morris (1986) explain that a mental model can be conceived as a cognitive structure that enables a person to describe, explain, and predict a system’s purpose, form, function, and state.

Everyone has mental models and as grant writers it is imperative we be aware of our mental models when we join a project. Oftentimes, we’re coming into projects where we know little about the norms and customs of a community. Yet, we’ve been brought into the project to represent that very community we have such little firsthand experience about. We need to quickly get up to speed to be a good representative.

A great way to gauge your mental model is to consider how you’re approaching a community and how you’re representing them in a narrative. Does it match how they want to be represented? If you were a community member, is it how you would want to be represented?

Dig a Little Deeper

It is appealing to focus only on the problem(s) we see within the community—maybe it is the extremely low high school graduation rate. But, will that be the drive of the narrative? Is there an opportunity to switch to a different mental model? Look beyond data that feeds a deficit-based approach.

As grant writers, we don’t always have an abundance of resources to invest in learning about a community’s strengths. It should be comforting to know that you don’t necessarily have to dig to the depths of the earth, but just far enough to build strength-based thought into the narrative.

Again, we must still define the problem of low high school graduation rates, but can we shift our perspective and thinking just a bit? What is the community doing well? We can expose ourselves to other data through additional research or by talking with program staff or community members. Perhaps that data or those conversations reveal that this particular community is especially connected to climate and the environment. Any education or coursework involving the climate goes over well for students because they get it.

Instead of simply stating the problem and throwing yet another program at the community, talk with the community about it. Examine what currently exists and how those resources might be bolstered. Perhaps the greater community of elders, healthcare providers, or education professionals can be engaged in the conversation to address low graduation rates.

Now we’re toeing the line of program and project development. As a grant writer, much of the project development and planning process will be outside of your purview. You may help certainly, as needed for each client, but the bulk of the work will be done by your client. Writing the grant will be infinitely smoother if the client is on board with a strength-based approach.

You might consider having a conversation with the client at the initial kick-off meeting to introduce a deficit-based versus strength-based approach. This can become a natural part of your process with every project and every client. When the client is delivering to you projects that are saturated with strengths, your writing in the narrative will reflect that (and same goes if they were delivering deficit saturated projects).

The table below is a perfect example of what it might look like to dig deeper and shift our mental models.

| Deficit-Based Mental Model | Strength-Based Mental Model |

|---|---|

| Implement programs as the answer | See people as the answer |

| Us versus them | In this together |

| Assumes dependence | Increases sustainability |

| Focus on what is broken | Focus on what is working |

P.S. We break these concepts down in our book, How to Write a Grant: Become a Grant Writing Unicorn, as well.

Grant Writing Unicorn Book

#1 bestseller on Amazon for nonprofit fundraising and grants. Do you have a copy of, “How to Write a Grant: Become a Grant Writing Unicorn”?

Get a Copy Now

Using Logic Models to Inform Strengths

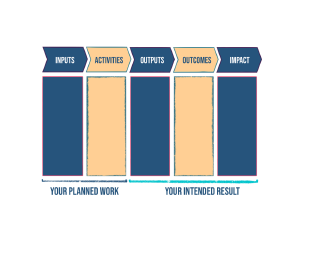

An excellent way to evaluate an organization’s strengths is through the use of logic models. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a logic model is a “graphic depiction (road map) that presents the shared relationships among the resources, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impact for your program. It depicts the relationship between your program's activities and its intended effects.”

In short, a logic model is a planning and accountability tool. It allows organizations to keep track of their work and offers a continuous feedback loop about where they’re at on the road map. The nuts and bolts of a logic model are inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes (short-term, mid-term, and long-term/impact).

Inputs are new and existing resources that will be used to support the project (examples: funding, project team, partnerships, etc.).

Activities include the main things the project will do (examples: holding workshops, trainings, or camps).

Outputs are the products that will be created (examples: flyers, pieces of art, artifacts).

Short-term outcomes are what will happen as a direct result of the activities and outputs. Typically these are changes in knowledge, skills, and/or attitudes (example: youth increase their understanding of protective factors).

Mid-term outcomes are the results that will follow from the initial outcomes. Typically these are changes in changes in behavior, policies, and/or practices (example: youth engage in relationship building with a positive, trusted adult).

Long-term outcomes are the results that should follow from the short-term and mid-term outcomes. You might also consider these results to be your impact. Typically these are changes in changes in broader conditions (example: youth are more resilient and have lower rates of depression or self-harm).

Evaluating projects through logic models serves to help us identify major gaps and significant strengths in our processes. Once those are identified, we can continue developing our projects to evolve with our needs and existing strengths. This then plays directly into a strength-based approach to writing future grant narratives.

To learn more about logic models, check out a training on evaluation that Kate Hohman Billmeier graciously provided for us on our YouTube page: Grant Evaluation - How to Measure the Impact of Your Grant-Funded Project.

Strengths Based Approach to Social Work

As you’re working through your logic models, one way to use strong language is to focus on systems rather than individuals. Axel-Lute said that, “The way to avoid the problem of having the struggles of individual people or places represent something inherent and immutable is to explicitly point out the systems at work—past and present—that cause them.”

When you’re describing a problem, use language that highlights how systemic disparities and a history of community (city, region, state, nation) wide problems have systemic roots. Emphasize how those root causes have created harm, that these are not self-caused problems, and work to clearly explain those systems as much as possible. A systemic approach like this connects deeply with many progressive funders.

For example, the Ford Foundation’s funding priority model completely encompasses an awareness and recognition on systems as it relates to inequality. They strive to disrupt systems to advance social justice. The Ford Foundation has identified five underlying drivers of inequality—common factors that, worldwide, contribute to inequality’s many manifestations.

These factors are:

- Entrenched cultural narratives that undermine fairness, tolerance, and inclusion.

- Failure to invest in and protect vital public goods such as education and natural resources.

- Unfair rules of the economy that magnify unequal opportunity and outcomes.

- Unequal access to government decision making and resources.

- Persistent prejudice and discrimination against women, people with disabilities and racial, ethnic, and caste minorities.

Are any of those factors relevant to the community you’re serving? How might your next grant application benefit from emphasizing one or more of those factors?

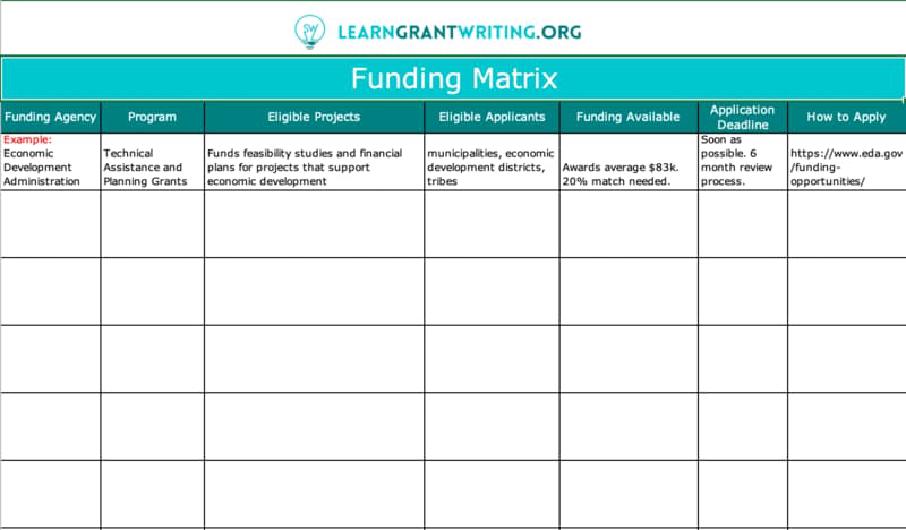

Free Grant Matrix Template

To stay organized, we recommend you put your grant findings in a matrix. This way you can systematically filter the top pursuits.

Get Free Grant Matrix Template

Overcoming Challenges

Getting into the habit of gravitating toward strength-based writing and thinking is the same as getting into any habit: it takes practice. Your mindset is hugely important as you flex your new muscles. Adopting a more strength-based approach to developing grant proposals is a philosophy. It’s more than just words; it’s a shift in whole mental models.

Another tool that might be useful for you is to develop a short list of questions to ask yourself throughout the grant writing process. Refer to these customized questions at the beginning of the project and intermittently throughout the project to ensure you’re on track. Perhaps a few questions you might ask yourself include:

- Does my representation of the community match how the community wants to be represented?

- If I were a community member, is it how I would want to be represented?

- What story am I telling? What is the focus of that story?

- What is the community doing well? What is working?

- Am I using positive language in the narrative?

- Have I spoken with community members?

- Am I telling the whole truth?

Final Takeaway

So, is this rocking your world yet? Do you feel like you’ve been thinking and writing the wrong way? Yeah, that’s sort of how we felt too. Thank goodness we are all in this together, and that we are all continuously in process.

When we only emphasize negative statistics and disparities, we define people and places by their worst characteristics. Ironically, using deficit-based language risks reinforcing the same negative stereotypes that organizations are fighting against. Yes, it can sometimes feel like it is an entire system we’re up against. As Axel-Lute said, this “can contribute to a dynamic where people and places are treated less as partners in a given program or campaign and more like objects of charity.”

When you write your narrative, be on the lookout for deficit-based thinking that could be reworked to present a more strengths-based approach. Consider Pareto’s Principle when writing, so that deficit-based writing accounts for roughly 20% of your narrative and strengths-based writing accounts for the other 80%.

Finally, give yourself grace as you work to make this shift. This is a difficult balance, but one we have committed to working on and we hope you do too. It will take practice and a lot of trying again. That’s normal, and you can do it.

Grant Writing Resources

Serious about becoming a grant writer? Learn about our online grant writing training course.

If you don't already, be sure to follow us on Instagram.

Free Grant Writing Class

Learn the 7-steps to write a winning grant application and amplify the impact you have on your community.

Access Free Class